Thread

The evolution of the American lecture circuit is fascinating. It is way undervalued as a factor in shaping American culture and society.

Took me forever to realize that historians were calling the same thing by different names, because it varied depending on the decade, region, and socioeconomic class. The Lyceum Movement is presented as almost unrelated to the contemporaneous lecture craze among MA elites.

It's like each manifestation was perceived as a national, uniform movement, unaffected by local culture and circumstances, which was therefore mutually exclusive with all the others. It was more like an evolving network of subcultures that later got professionalized by Bureaus.

The Lyceum Movement was a way of building political alliances in rural or frontier towns, so it was for ambitious, respectable young men. In MA, it was a form of intellectual and religious exploration, so it attracted the well-read and eccentric members of the entire community.

Then in the late 1860s, these merge into something like "Radical Republican high culture," the last gasp of abolitionism and classical political oratory, which reflected the liberal nationalism of the victorious Northeastern Republican elites.

Unsurprisingly, this circuit was managed by the newly formed Boston Lyceum Bureau. Scholars of abolitionism often reference it without bothering to explain why American high culture is suddenly dominated by genteel, aging radicals with extremely liberal social views.

The Boston Lyceum Bureau was run by James Redpath, a New York Tribune journalist and anti-slavery activist. He was a native of Scotland, and evidently fearless. His first assignment was visiting the South in 1854 to interview slaves and "collect information" about slavery.

The next year, he moved to the Kansas-Missouri border to cover "the dispute over slavery in Kansas Territory." For the next three years, "he was active in Kansas affairs, engaging in politics, writing dispatches..."

"... securing support in New England for Free Soil settlers, and writing poetry about Kansas. In 1856, he interviewed John Brown just days after the massacre at Pottawatomie Creel...he became Brown's most fervent publicist."

"In 1858, Brown encouraged Redpath to move to Boston to help rally support for his plan for a Southern slave insurrection." After Brown was executed, Redpath memorialized him in a "highly sympathetic" biography.

During the war, Redpath "abandoned publishing to serve as a war correspondent with the armies of George Henry Thomas and William Tecumseh Sherman in Georgia and South Carolina. In February 1865, federal military authorities appointed him the first superintendent..."

"...of public schools in the Charleston, South Carolina, region. He soon had more than 100 instructors at work teaching 3,500 African-American and white students. He also founded an orphan asylum."

"In 1868, Redpath started one of the first professional lecturing bureaus in the country, the Boston Lyceum Bureau...it supplied speakers and performers for lyceums all across the country." Who did it send?

Julia Ward Howe, Sumner, Emerson, Phillips, Beecher, Douglass, etc.

Most of the lecturing was done in the Midwest. The material was didactic and unoriginal enough that it had to be aimed at the rising middle class. Sumner's 1867 lecture topic was "Are We a Nation?"

Most of the lecturing was done in the Midwest. The material was didactic and unoriginal enough that it had to be aimed at the rising middle class. Sumner's 1867 lecture topic was "Are We a Nation?"

That lasted until the early 1870s, when the Radical Republicans and the culture they exemplified fell. It is replaced by the so-called "Chautauqua Movement." Once you zoom out from Progressive-Era NY, it doesn't look like a strange new national movement for rural people.

Instead, it looks like an attempt to brand and commercialize the mid-century lecture circuit model of adult education/self-culture, which had returned to its grassroots form in the cities and suburbs of the Northeast and Midwest after 1876.

The Chautauqua branch of the lecture circuit was old, and one of the most intellectual ones, but it had been overshadowed by the prestige of the Boston and NYC branches. It filled the void when "serious" adult education moved into the professional institutions and universities.

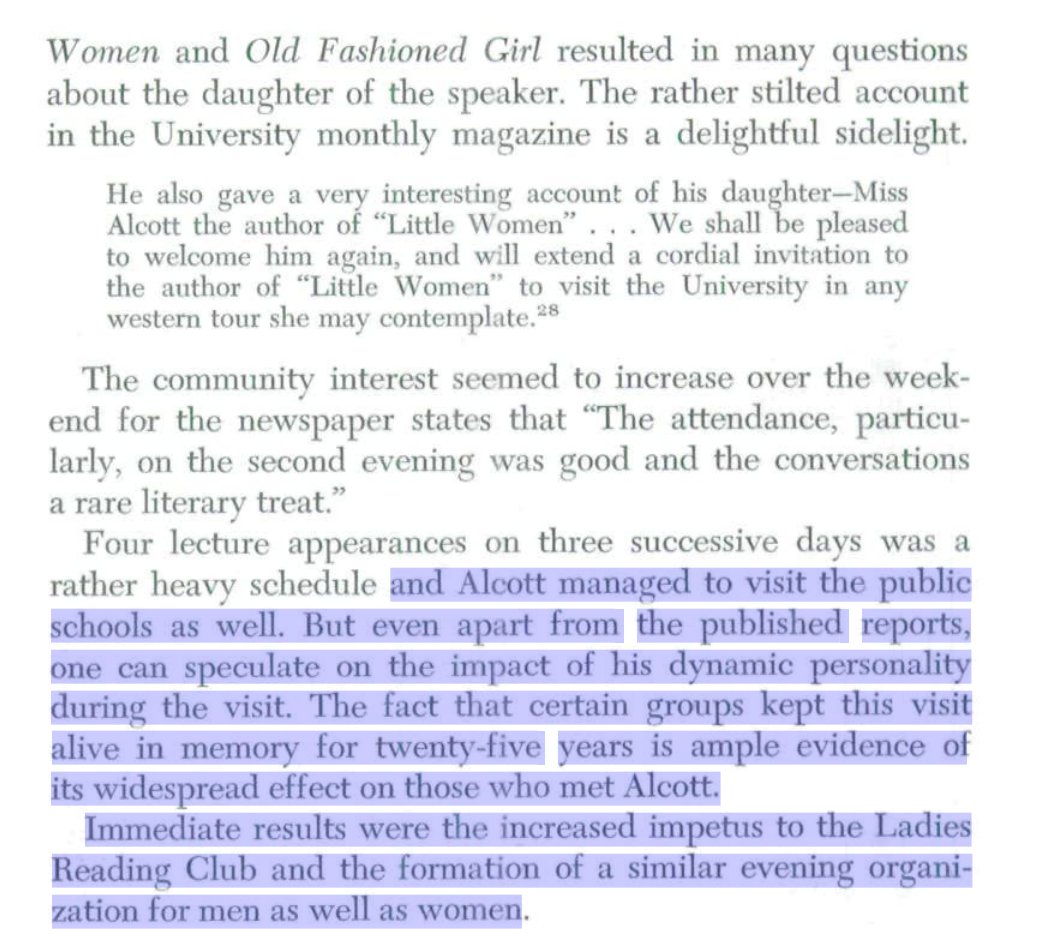

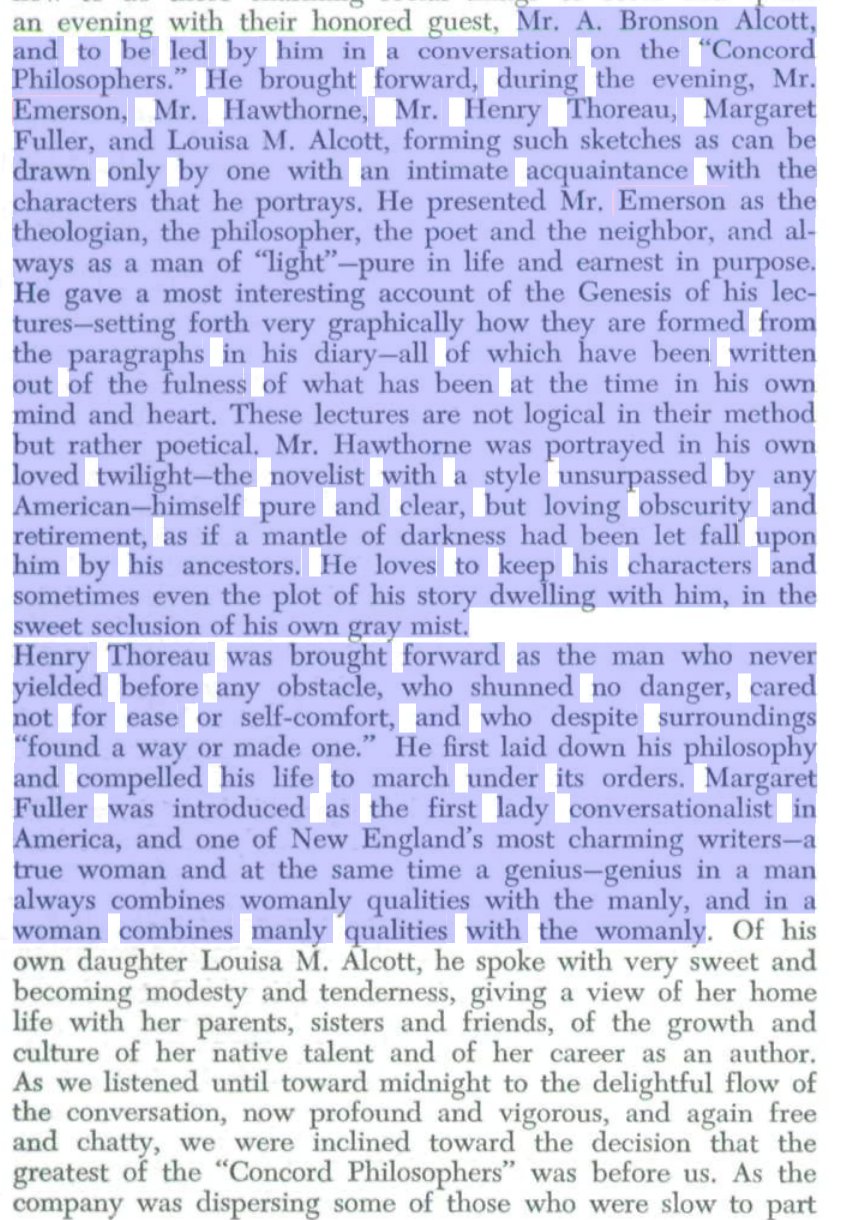

As a result, the main audience became women and young people just entering the middle or upper-middle class. It skewed heavily towards entertainment, reminiscences, new (alleged) discoveries, and self-culture. What's hilarious is that this is the high-point of Alcott's career.

"In the 1890s, both Chautauqua and vaudeville were gaining popularity...While Chautauqua had its roots in Sunday-school and valued morality and education highly, vaudeville grew out of minstrel shows, variety acts, and crude humor..."

"...and so the two movements found themselves at odds. Chautauqua was considered wholesome, family entertainment and appealed to middle classes and people who considered themselves to be respectable or aspired to respectability...."

"...Vaudeville...was considered by many to be vulgar and appealed to working class men. There was a stark distinction between the two, and neither generally shared performers or audiences."

If you conflate the two, it looks like a sudden outburst of bigoted anti-intellectualism.

If you conflate the two, it looks like a sudden outburst of bigoted anti-intellectualism.

"Entertainers on the Chautauqua circuit such as...'The Man From Vermont' and 'The Old Country Fiddler', played violin, sang, performed ventriloquism and comedy, and told tall tales about life in rural New England."

Alcott did a more "intellectual" version of this.

Alcott did a more "intellectual" version of this.

The WP page suggests that different things have been conflated.

"'Circuit Chautauquas'...were an itinerant manifestation of the Chautauqua movement, founded by [a Boston] Lyceum Bureau manager...[Chautauquas didn't have any] central authority over them."

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chautauqua

"'Circuit Chautauquas'...were an itinerant manifestation of the Chautauqua movement, founded by [a Boston] Lyceum Bureau manager...[Chautauquas didn't have any] central authority over them."

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chautauqua

"The great number of Chautauquas, as well as the absence of any central authority over them, meant that religious patterns varied greatly...Some were...essentially church camps, while more secular Chautauquas resembled summer school and competed with vaudeville...."