Thread

Time and again, we find that some neural phenomenon that initially seems to have one function also contributes to the 'opposite' function.

The zero-order response is to be skeptical of attributing any function in the first place. But perhaps there is a dialectical solution...

The zero-order response is to be skeptical of attributing any function in the first place. But perhaps there is a dialectical solution...

... that recognizes how seemingly opposed forces actually cooperate and enable each other. So rather than rejecting functional explanations, we have to 'suspend' them in a broader notion of function, viewing each partial function as a facet of a higher-dimensional 'object'.

...

...

Dopamine is a decent example. It was initially associated with reward (and association that pop culture seems unable to unlearn), but it is now well known that other experiences, such as stress, can also elevate dopamine.

...

...

One should not attempt to force the reward story onto the stress findings --- I'm sure some people hearing about such data will immediately contort their imaginations to view stress itself as rewarding. That's not always an incorrect mode, but we can perhaps do better.

...

...

It may well be that rewards (and often the more narrow notion of reward-prediction error) and stress are different low-dimensional projections of a higher-dimensional process of labeling affective salience.

This too is of course a speculation that may be wrong.

...

This too is of course a speculation that may be wrong.

...

But I think it is better to move forward with semantically meaningful speculations than to throw up one's hands and say "it's complicated" or "everything is connected to everything else".

Holistic stupor is not conducive to generating new testable hypotheses. :P

Holistic stupor is not conducive to generating new testable hypotheses. :P

Oxytocin is another good example of a failed functional story that escaped the laboratory and began breeding. @edyong209's has written eloquently and forcefully about the dangers of calling it the love hormone.

...

www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2015/11/the-weak-science-of-the-wrongly-named-moral-molecule/4155...

...

www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2015/11/the-weak-science-of-the-wrongly-named-moral-molecule/4155...

Oxytocin was initially associated with care and parental instincts, but it has also been linked with aggression.

I am not even close to being an expert on oxytocin, but as a computational modeler I think there are interesting avenues to explore here.

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28864975/

I am not even close to being an expert on oxytocin, but as a computational modeler I think there are interesting avenues to explore here.

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28864975/

Sometimes it is useful to think of chemicals and other signals as "unsigned" amplifiers. Here "unsigned" means that they amplify both "positive" and "negative" (or "appetitive" and "aversive") processes. There are various reasons why this type of control *might* be useful.

....

....

One way to think about "unsigned" amplification is as a way to raise urgency for *whatever* salient behavior might be most relevant to the context. A more low-level function here could involve speeding up transitions between states, or even achieving the opposite.

...

...

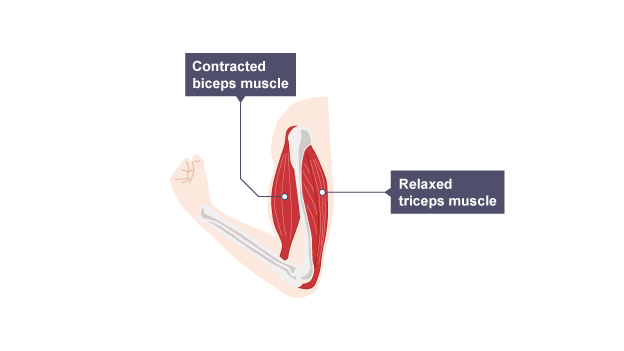

I often find myself taking inspiration from motor control. One of the most fascinating yet simple phenomena in basic motor control is opponent processing by muscles.

For moving a given joint, one often finds pairs of cooperating muscles: an agonist and an antagonist.

...

For moving a given joint, one often finds pairs of cooperating muscles: an agonist and an antagonist.

...

Bending the arm involves contracting the biceps and relaxing the triceps. Straightening it involves the opposite.

But there is another possibility: contracting both the biceps and the triceps. Why might we do that?

www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/guides/z8stfrd/revision/4

But there is another possibility: contracting both the biceps and the triceps. Why might we do that?

www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/guides/z8stfrd/revision/4

If we think in an excessively symbolic way, then opposing processes seem to cancel each other out, like positive and negative numbers of the same magnitude. But this leaves out the concept of stability in the face of perturbations.

...

...

Contracting opposing pairs of muscles is not a matter of canceling two equal and opposite forces. Instead, it enables a degree of rigidity: muscles do not only allow us to move, but also to stiffen and hold our positions when needed.

...

...

So by analogy, it may be that many seemingly opposed 'forces' in the brain cooperate not merely to 'move' neural patterns one way or the other, but also in the service of changing the 'rigidity' of existing patterns. (It's an easy jump from here to the notion of attractor depth.)

Neural processes that really do have 'contradictory' actions (meaning that this is not simply a matter of experimental error) may well be pointing us towards a richer sense in which opponent processes cooperate.

I should add that I have only scratched the surface here. Opponent processing of the sort I explain above is in a sense a one-dimensional phenomenon. Competitive dynamics in a neural field (either all-to-all or topographically organized) provides a higher-dimensional example.