Thread by Bryan Carmody

- Tweet

- Mar 13, 2023

- #History #Algorithm #Politics

Thread

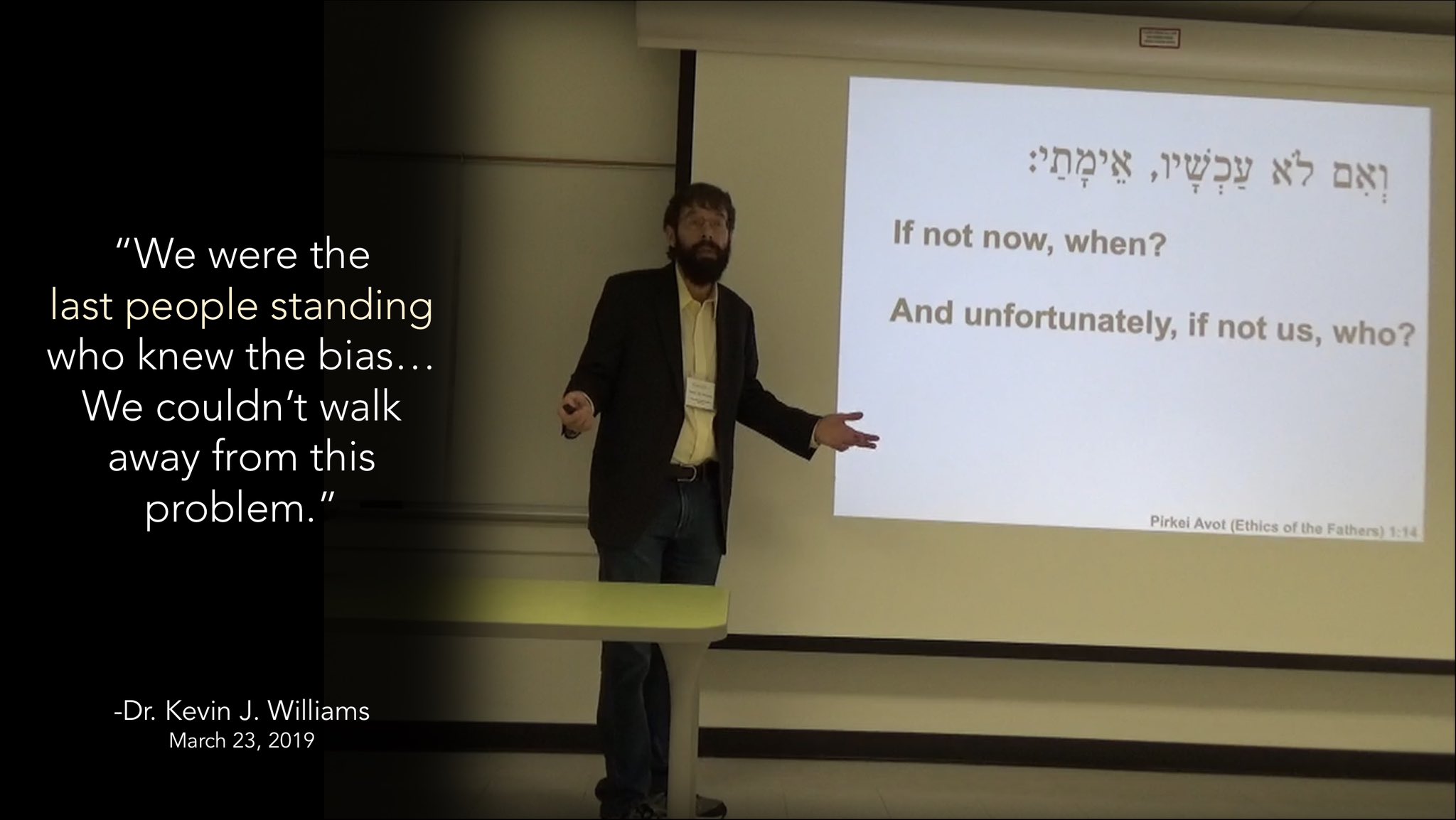

As we countdown to Match Day, I want you to meet Dr. Kevin Jon Williams.

For nearly 20 years, he fought for - and eventually won - a student-optimal matching algorithm.

It’s one of the great stories of advocacy in Match history… and the NRMP refuses to acknowledge it.

(a 🧵)

For nearly 20 years, he fought for - and eventually won - a student-optimal matching algorithm.

It’s one of the great stories of advocacy in Match history… and the NRMP refuses to acknowledge it.

(a 🧵)

Lemme explain.

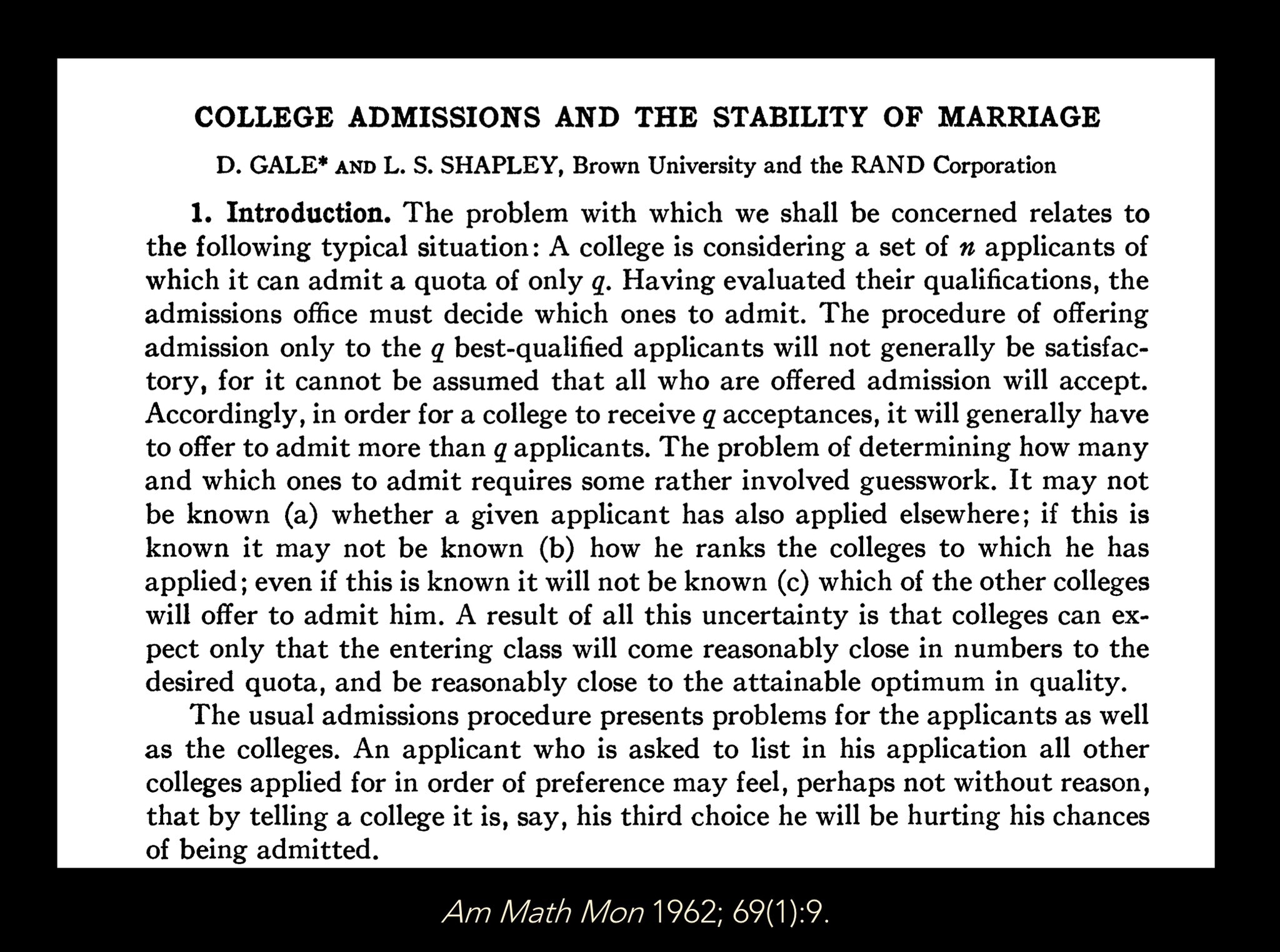

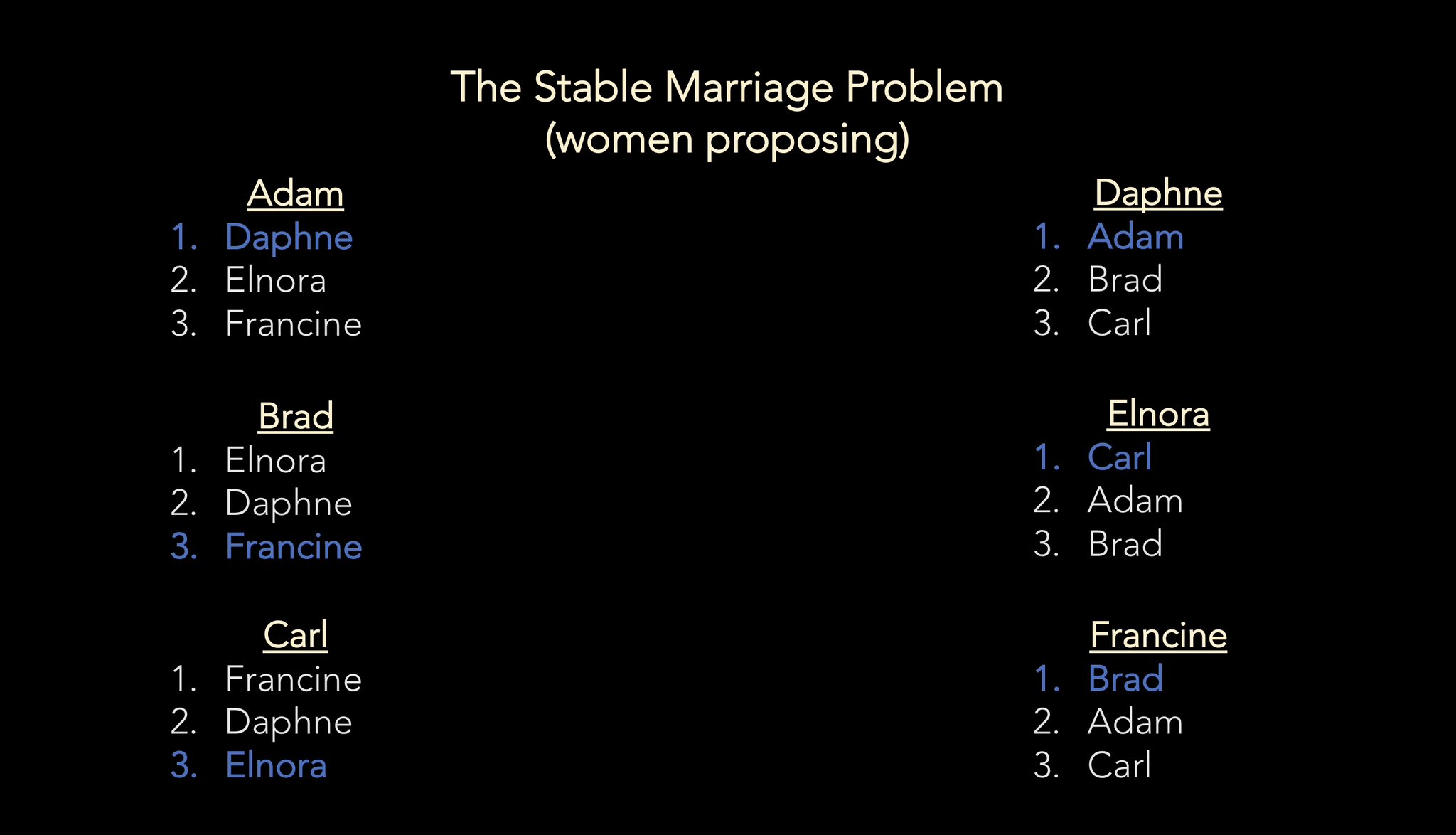

In 1962, mathematicians David Gale and Lloyd Shapley solved the “Stable Marriage Problem.”

By using a deferred acceptance algorithm, you could pair up a set of men and women who each wanted to be married, but had varying preferences among the potential partners.

In 1962, mathematicians David Gale and Lloyd Shapley solved the “Stable Marriage Problem.”

By using a deferred acceptance algorithm, you could pair up a set of men and women who each wanted to be married, but had varying preferences among the potential partners.

Importantly, Gale & Shapley’s solution resulted in STABLE pairings - meaning that there was no pair of man/woman who *both* wanted to be married to someone other than the partner that the algorithm assigned.

Although Gale & Shapley’s 1962 paper received lots of attention (leading to >10k citations and a Nobel Prize), the method they described was essentially the same as the one used by the resident match since 1952 - and had been devised by medical students.

youtu.be/_wGHG7QQmkU

youtu.be/_wGHG7QQmkU

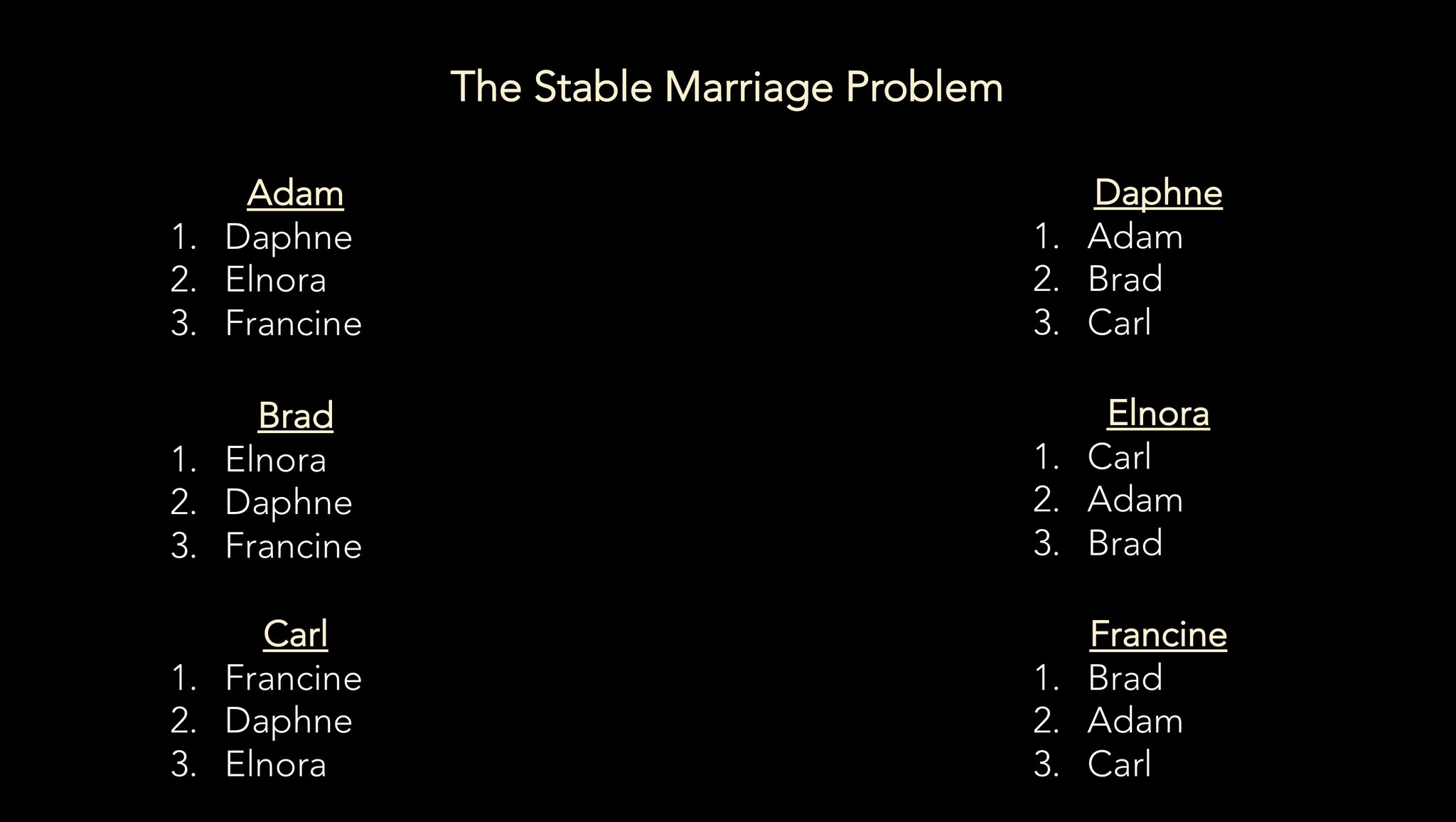

But Gale & Shapley showed that there wasn’t just one solution to the Stable Marriage Problem.

There were two.

They were mirror images of each other, and both resulted in stable matching. But which party got their *optimal* stable match depended on who proposed to whom.

There were two.

They were mirror images of each other, and both resulted in stable matching. But which party got their *optimal* stable match depended on who proposed to whom.

If the men proposed to the women, they got their optimal stable match.

If the women proposed to the men, they got their optimal stable match.

If the women proposed to the men, they got their optimal stable match.

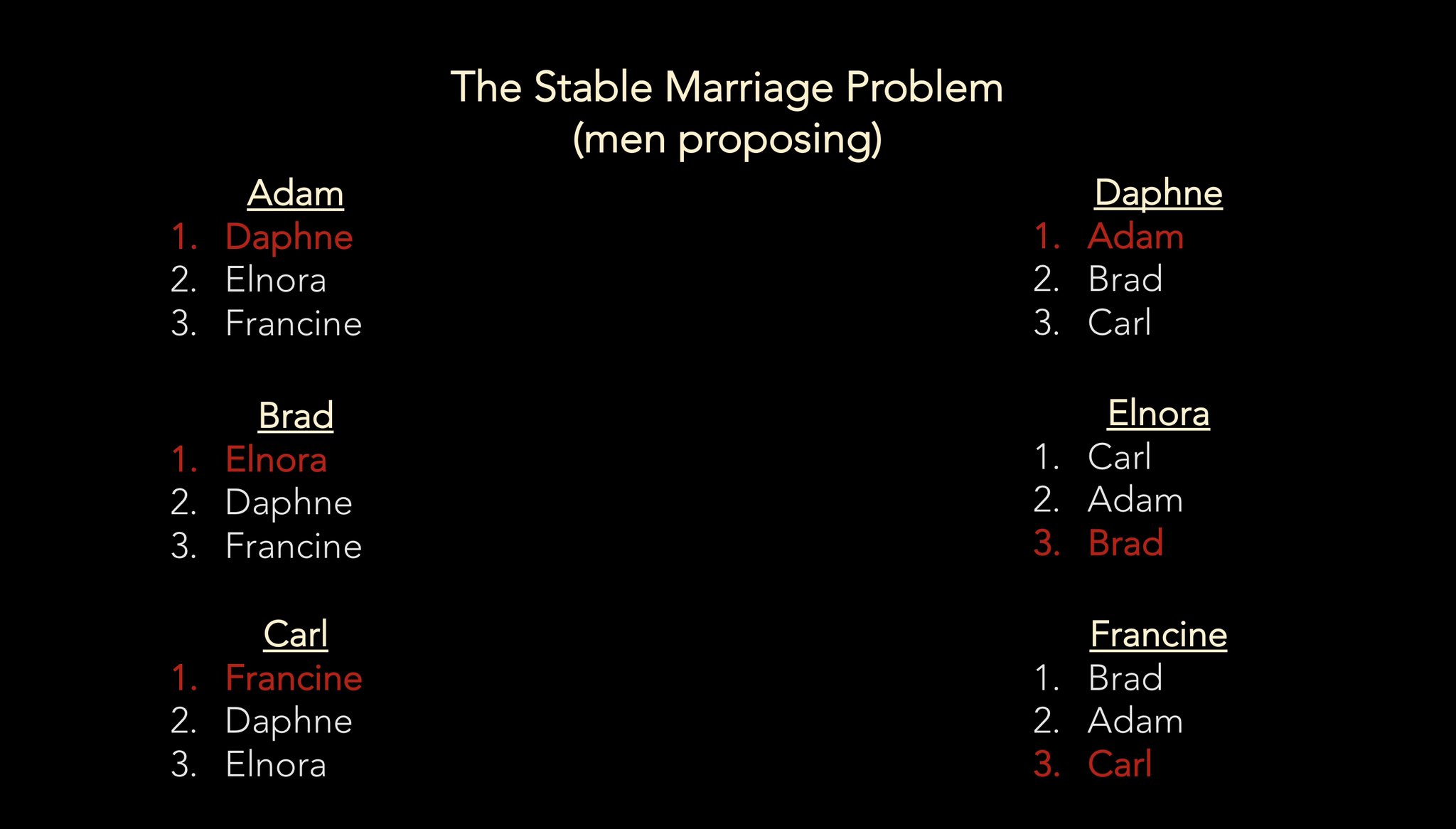

So you might wonder: how did the NRMP algorithm work?

Who ‘proposed’ to whom?

Who got the optimal stable match - programs or applicants?

Well, that’s exactly what Dr. Williams began to wonder about when he was a fourth year medical student.

(that’s him on the left)

Who ‘proposed’ to whom?

Who got the optimal stable match - programs or applicants?

Well, that’s exactly what Dr. Williams began to wonder about when he was a fourth year medical student.

(that’s him on the left)

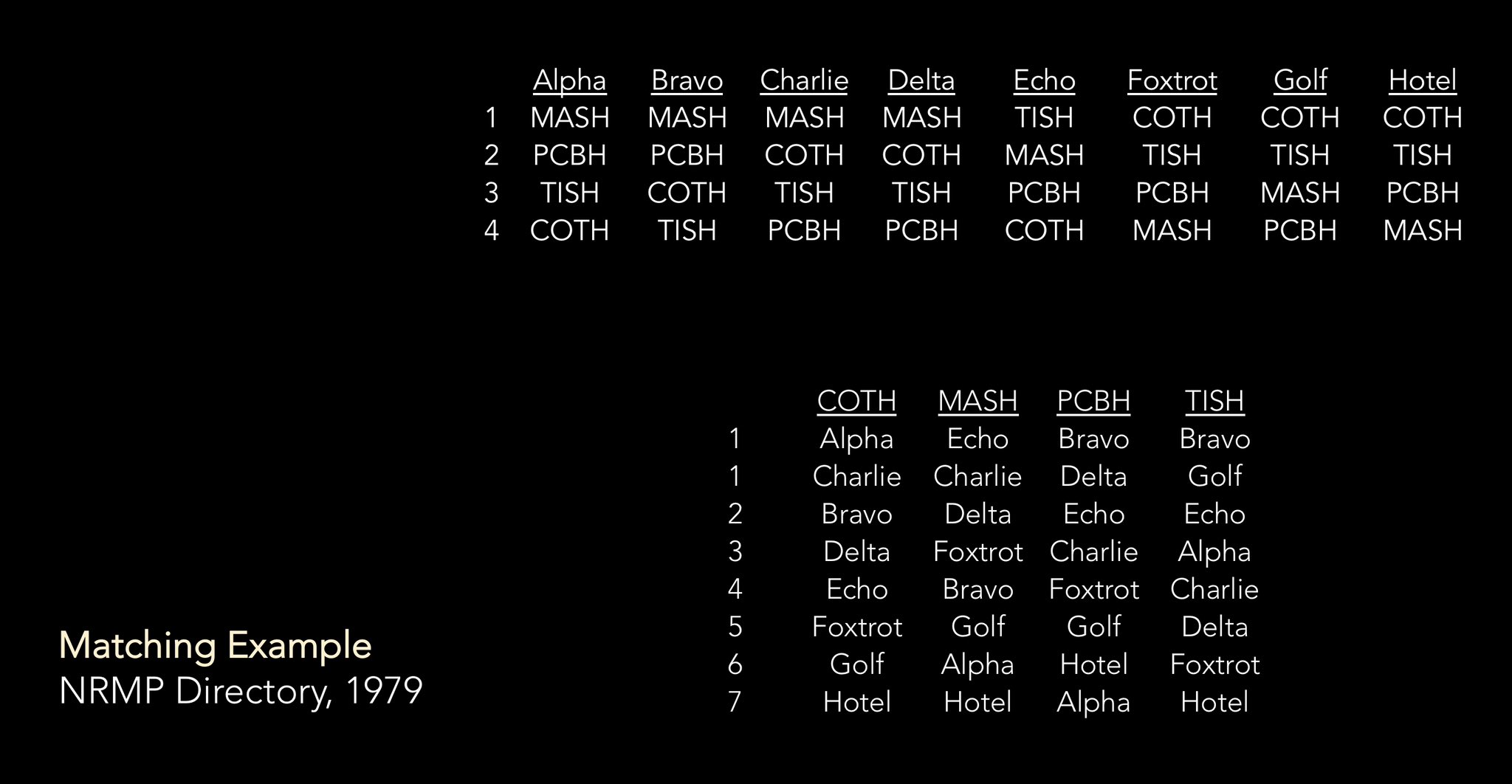

So he grabbed a copy of the 1979 NRMP Directory and worked through the example provided.

When he did, he came to a startling realization:

The NRMP algorithm was program-optimal.

When he did, he came to a startling realization:

The NRMP algorithm was program-optimal.

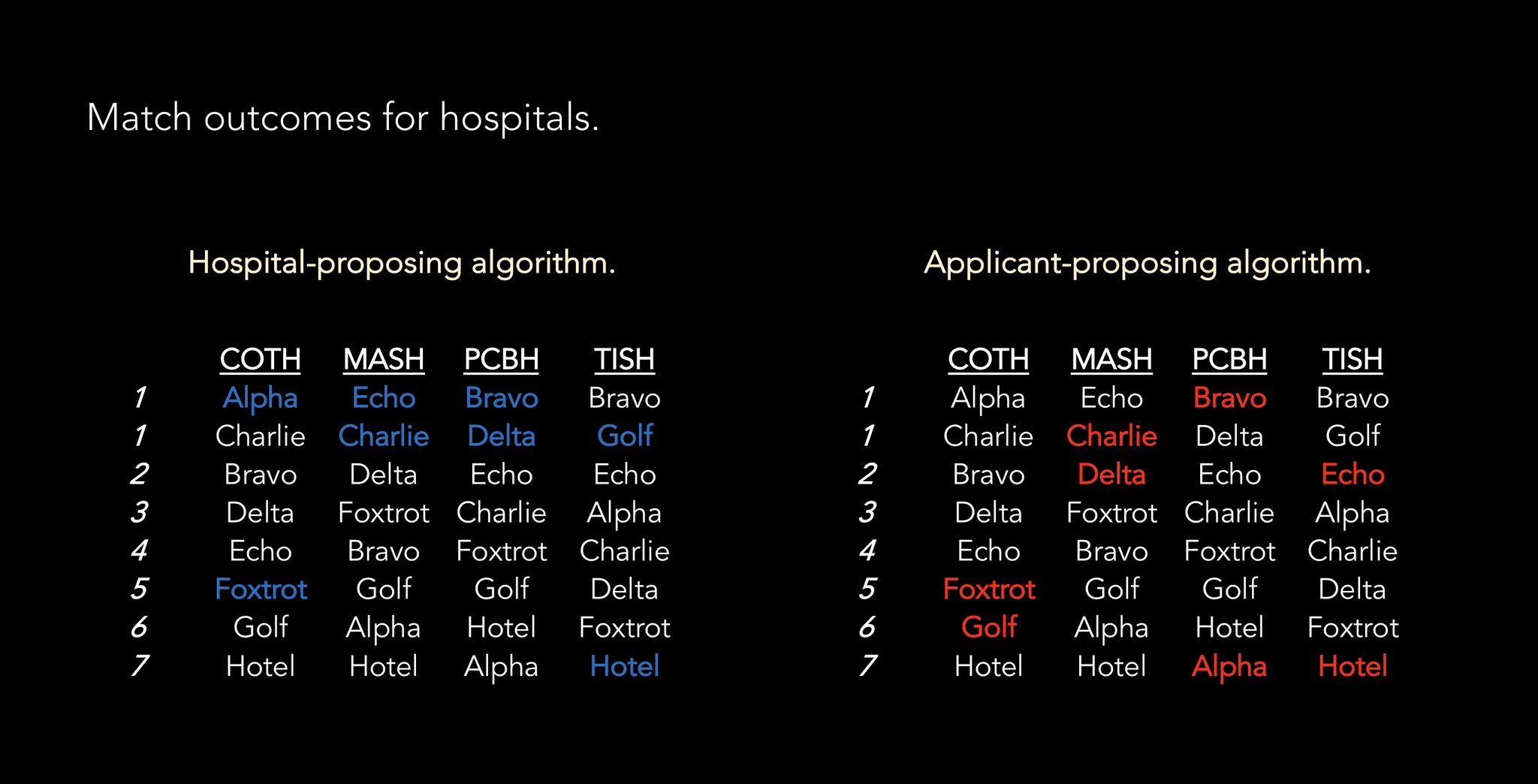

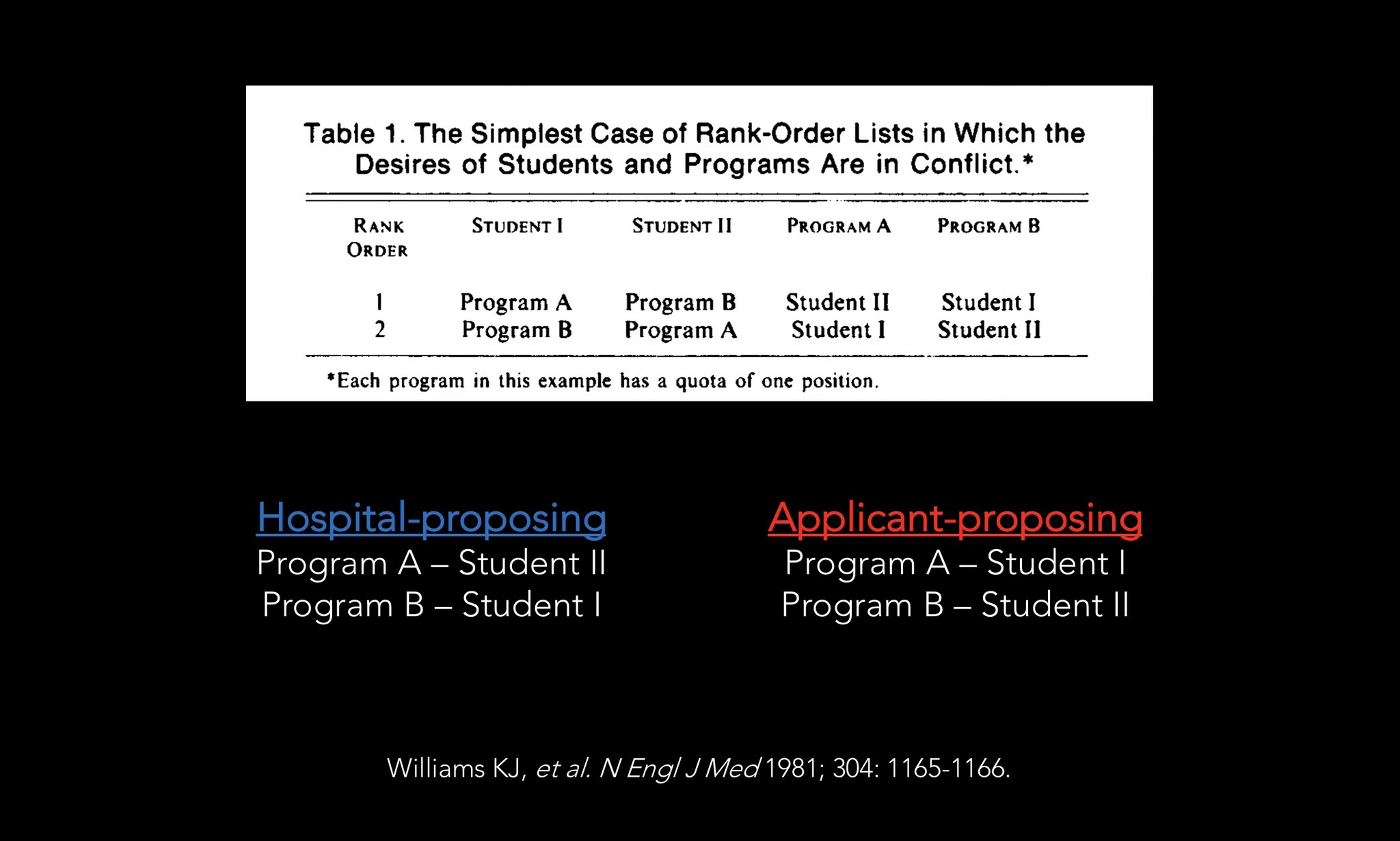

If you let hospitals propose matches to applicants, almost all of them end up with their top choice applicants. Look at all the blue at the top of their rank order lists.

If you let the applicants propose matches to the hospitals, the hospitals don’t do as well (red).

If you let the applicants propose matches to the hospitals, the hospitals don’t do as well (red).

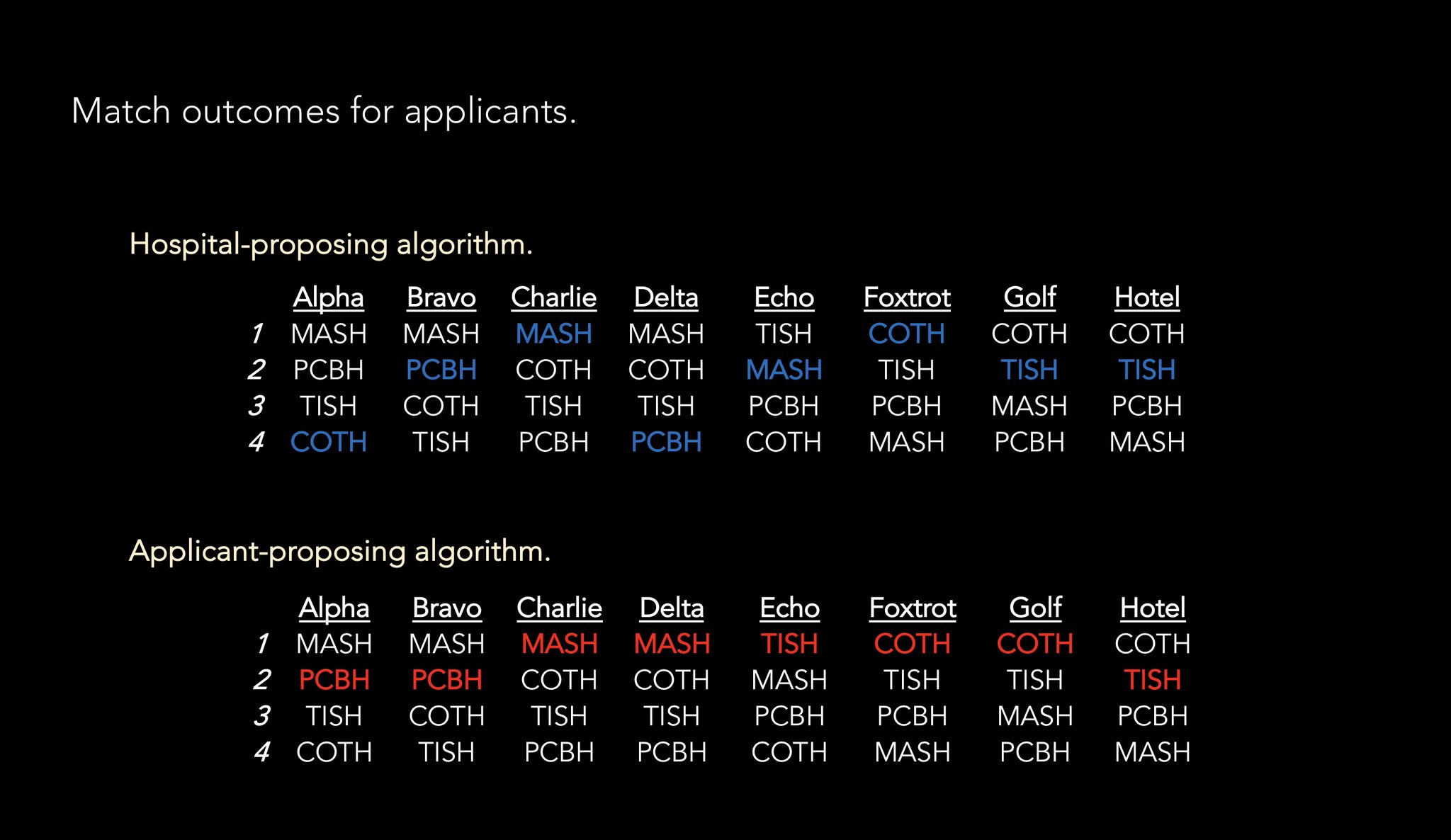

Conversely, every applicant got their #1 or #2 choice if you used an applicant-proposing algorithm (red).

If you used a hospital proposing algorithm, 25% of applicants got their last choice (blue).

If you used a hospital proposing algorithm, 25% of applicants got their last choice (blue).

Two things to remember.

1 - Both the applicant-proposing or the hospital-proposing algorithm generate stable matches. There’s no inherent reason to choose one over the other.

2 - This was the NRMP’s OWN EXAMPLE. It wasn’t some theoretical thing Williams made up.

1 - Both the applicant-proposing or the hospital-proposing algorithm generate stable matches. There’s no inherent reason to choose one over the other.

2 - This was the NRMP’s OWN EXAMPLE. It wasn’t some theoretical thing Williams made up.

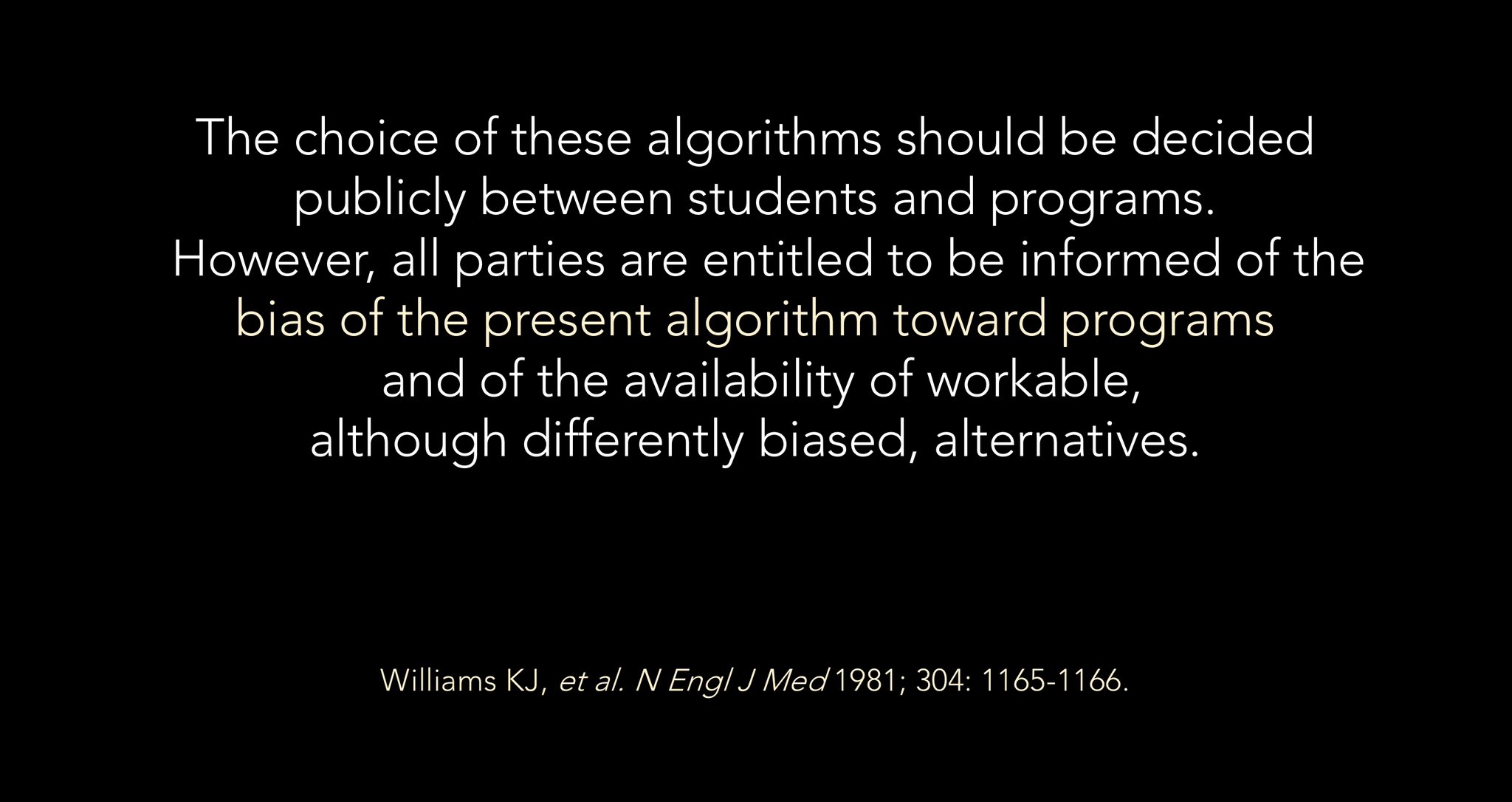

So Williams and his classmates pointed out this issue in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Their article concluded with the quote below.

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7219451/

Their article concluded with the quote below.

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7219451/

They assumed that by pointing out this issue in the most prestigious, highest impact journal in all of medicine, it would ignite a debate and that this issue would be resolved.

Or maybe the NRMP would study the issue, at least.

Instead, almost nothing happened.

Or maybe the NRMP would study the issue, at least.

Instead, almost nothing happened.

I say “almost nothing,” because the NRMP did do one thing.

They removed the matching example that had been in their 1979 Directory… with any technical description of how their algorithm worked.

They removed the matching example that had been in their 1979 Directory… with any technical description of how their algorithm worked.

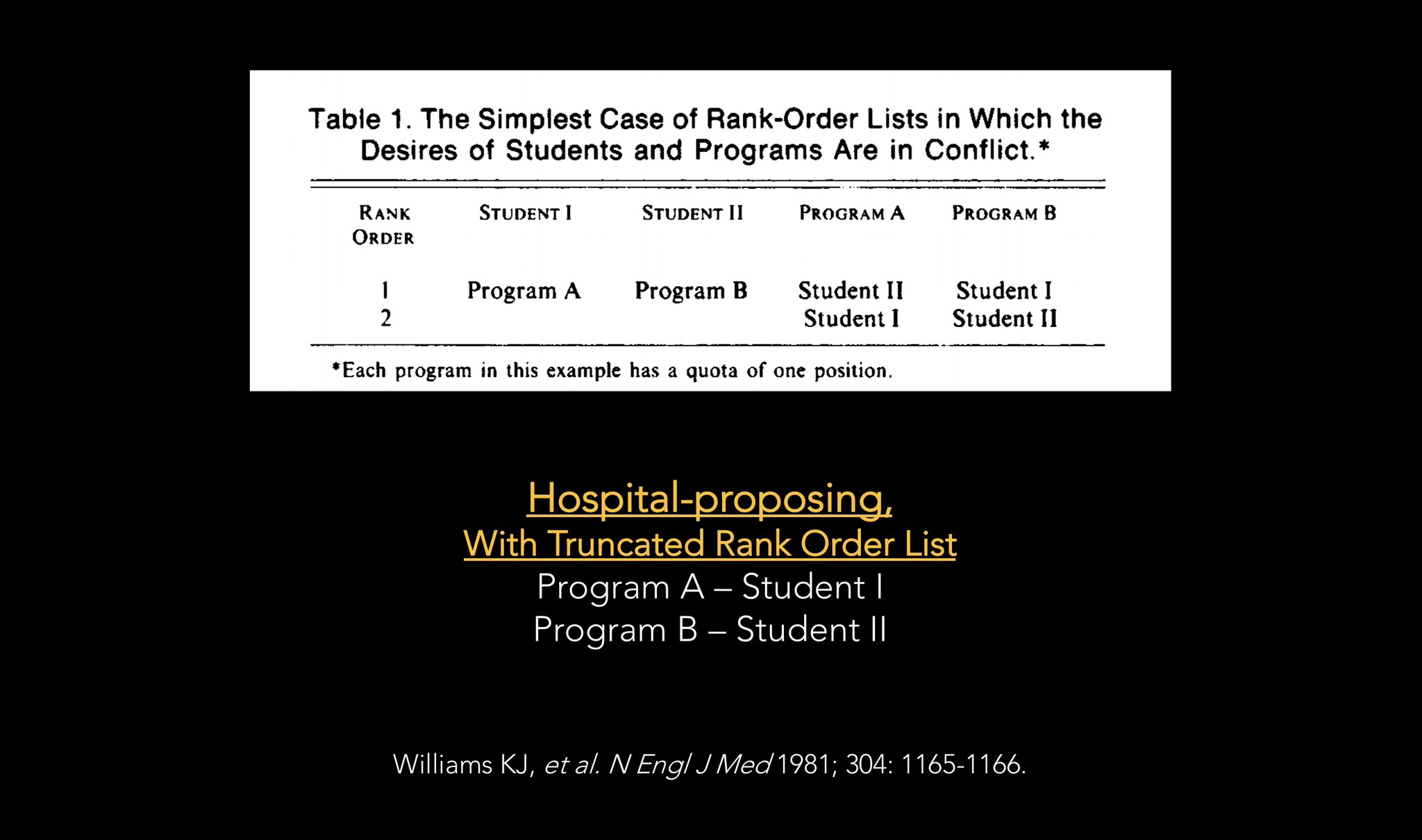

Instead, they told applicants that by ranking programs in their true order of preference, they’d get their best possible outcome.

Thing is, that wasn’t necessarily true.

Thing is, that wasn’t necessarily true.

Williams had shown in the 1981 NEJM article how it could be possible for applicants to get their top choice program under a hospital-proposing algorithm by SHORTENING their rank order list, leaving only the most desired program available to create a match.

But shortening the rank order list a dangerous strategy. It increases the risk of going unmatched, and isn’t we want to incentivize applicants to do.

So Williams set out again to get the NRMP to at least study how often a change in algorithm might result in a change in results.

So Williams set out again to get the NRMP to at least study how often a change in algorithm might result in a change in results.

By this point, he was a junior faculty member trying to make his way as a physician-scientist.

He had nothing to gain - and everything to lose - by taking on an entrenched bureaucracy.

Most of us would have walked away from this problem.

But Dr. Williams isn’t like most of us.

He had nothing to gain - and everything to lose - by taking on an entrenched bureaucracy.

Most of us would have walked away from this problem.

But Dr. Williams isn’t like most of us.

Every year, he’d submit another article on algorithmic bias.

Every year, the article would be rejected - usually after negative reviews by reviewers with connections to the NRMP.

And then, he had a breakthrough.

Every year, the article would be rejected - usually after negative reviews by reviewers with connections to the NRMP.

And then, he had a breakthrough.

The editor of @AcadMedJournal agreed to have an independent mathematician review the article - and to publish it if the independent reviewer said it was legit.

The article was published in 1995, and went off like a bombshell.

Soon, student groups and consumer advocates (like @RalphNader’ s Public Citizen) were calling upon the NRMP to study the impact of an algorithm change.

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7786366/

Soon, student groups and consumer advocates (like @RalphNader’ s Public Citizen) were calling upon the NRMP to study the impact of an algorithm change.

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7786366/

Finally, the NRMP commissioned Professor Alvin Roth to examine the issue.

The results were published in 1997 and were reassuring. The preferences of programs and applicants were so closely aligned that the choice of algorithm didn’t make much difference.

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9286832/

The results were published in 1997 and were reassuring. The preferences of programs and applicants were so closely aligned that the choice of algorithm didn’t make much difference.

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9286832/

Still, to remove the incentive for applicants to shorten rank order lists, the NRMP changed to the applicant proposing algorithm.

Ever since, applicants know with certainty that they can rank programs in their true order of preference and will get their best possible result.

Ever since, applicants know with certainty that they can rank programs in their true order of preference and will get their best possible result.

For whatever reason, @TheNRMP refuses to acknowledge this part of their history.

You won’t find any mention of Williams’ advocacy in their self-congratulatory “70th Anniversary of the Match” programming.

www.nrmp.org/about/news/2023/03/nrmp70-2/

You won’t find any mention of Williams’ advocacy in their self-congratulatory “70th Anniversary of the Match” programming.

www.nrmp.org/about/news/2023/03/nrmp70-2/

In a 2021 piece celebrating the NRMP’s “sustained partnership with learners,” Williams is neither mentioned nor his works cited.

Instead, the switch to an applicant-proposing algorithm is characterized as just another “learner-centered change” done by a benevolent NRMP Board.

Instead, the switch to an applicant-proposing algorithm is characterized as just another “learner-centered change” done by a benevolent NRMP Board.

Continued here…