Collection

My 13 Favorite Locked Room Mysteries

As promised in my recent essay on locked room mysteries, I’m sharing a list of my 13 favorite examples of this subgenre.

This is one of the earliest locked room tales, and it rivals even the best of Poe. I’m not surprised that, when pundits rank the best mysteries of all time, Futrelle’s short story is often found near the top of the list. The protagonist is Professor Augustus S. F. X. Van Dusen, whose nickname is the Thinking Machine, and he boasts that no problem is too great for the properly trained human mind. Two friends challenge the Professor to prove his claim in an ingenious experiment. The Thinking Machine will be incarcerated in an isolated cell in a high security prison. He has exactly on week to escape. He succeeds, of course, and even toys with the warden and guards along the way.

Here’s another locked room mystery that is as compelling a page-turner as anything you will find in the current day. Both Agatha Christie and John Dickson Carr have extravagantly praised this novel, and justifiably so. When I read this book, I was already familiar with Leroux from his more famous novel The Phantom of the Opera. But I will stake the perhaps controversial claim that The Mystery of the Yellow Room is even better than that classic story. Two sleuths compete with each other to solve a seemingly unsolvable crime—a locked room mystery that matches amateur detective Joseph Rouletabille against France’s most famous investigator Frédéric Larsan. Leroux initially published this novel as a magazine serial, and managed to keep the surprises coming at regular intervals for the full duration of his novel. The only unsolved mystery at the conclusion is why this story hasn’t been adapted for American audiences in a full-length movie or miniseries (although several French films have been based on it).

This is one of Agatha Christie’s finest works, paying homage to the locked room genre while adding some surprising new twists. There’s really no locked room here, merely a train carriage on the Orient Express halted by snowfall. But the constraints are similar: A murder takes place, but during a time when no one could have entered or left the train. The suspects are a motley assortment of passengers, but each new clue seems to make it more unlikely that any of them could have committed the crime. I’m not surprised that this story has been adapted for film, TV and radio on so many occasions. Even by Christie’s elevated standards, it’s a masterful work.

If you went to school to learn how to write locked room mysteries, this book would earn you a PhD, not to mention a publishing contract. Carr knew every possible trick in the genre, and his novel is filled to the brim with them. There’s also a lecture on the nature of locked room stories and ‘perfect crimes’ inserted into the narrative (in chapter 17) that can stand alone as a work of literary criticism. They should assign it in college lit crit classes, and perhaps at the police academy too.

There’s that man again! Almost at the same time as he released his classic The Hollow Men, John Dickson Carr published another formidable locked room mystery under his pseudonym Carter Dickson. The plot isn’t quite as elaborate as some other efforts, but here he showcases his knack for horror and suspense. His ability to combine intricate story construction with eerie atmospherics is unsurpassed in genre fiction, as this book still demonstrates almost ninety years after its initial release.

Who could be better at solving a crime involving impossible entries and exits than a famous stage magician? Hence Clayton Rawon introduces The Great Merlini, who makes his debut in this fast-paced novel from the 1930s, the finest decade for the locked room genre. Rawson has as many tricks up his sleeve as Merlini himself, and this book is as enjoyable for the asides and discursive passages—on everything from yoga to geometry—as for its sleuthing.

My introduction to this story came about when I played the role of Inspector Blore in a high school dramatic production of And Then There Were None. That was the last time I acted on stage—our director, a frustrated Hollywood actor reduced to coaching students of tender years, was brutal in scheduling endless rehearsals and lamenting our questionable Thespian skills in pointed monologues of remarkable acerbity. I decided I’d rather be locked away on a remote island with a potential murderer than go through more of that grief, hence I never auditioned again—but I still love Agatha Christie’s devilish story. Once again, she recreates the strictures of a locked room without needing any locks. The tale takes place on a (you guessed it) remote island where a group of visitors have arrived, each having received a mysterious invitation—only to find that, one-by-one, they’re getting murdered. The reader is in a race to determine the killer before only one candidate is left standing—who must be the obvious culprit (or maybe not?).

Can you combine classic British drawing room comedy with locked room sleuthing? Of course you can, and Christianna Brand succeeds on both counts. Suddenly at His Residence presents you with a dignified country estate straight out of Evelyn Waugh or P.G. Wodehouse, with all the competing family agendas that animate a classic comedy of manners. But the murder of Sir Richard is no laughing matter. There are so many likely suspects—because this patriarchal figure was constantly changing his will to punish and reward foes and favorites. But, of course, the heinous crime took place behind locked doors, with no trace of entry or departure.

The Ellery Queen stories deserve a revival of their own. They rank among the most carefully plotted tales in the whole detective canon. These whodunits were the work of a partnership between Frederic Dannay and his cousin Manfred Bennington Lee—the former specializing in constructing the crimes and clues, while the latter took on responsibility for turning them into slick mass-market narratives. In an odd metafiction twist, the duo used the pseudonym Ellery Queen—who was also the detective in the stories. The King is Dead is one of their best efforts, full of the zip and energy of mid-century pulp fiction, but with amusing characters and one of the wildest locked room premises I’ve read. It’s all a bit goofy and dated, but even today you could turn this into a fun and campy film.

Seishi Yokomizo is sometimes called the “Japanese John Dickson Carr,” and this is the book that established his credentials as a master of the locked room mystery. The detective who solves this case, Kosuke Kindaichi, proved so popular that Yokomizo would feature him in another 75 novels—which have sold in aggregate more than 5 million copies. This is an extremely intricate story, with many moving parts contributing to the solution. In Japan, these elaborate tales are called honkaku mysteries, and the word honkaku translates as “orthodox.” But it might be better to describe them as mind-boggling logic problems dressed up as a crime narratives. This is one of the finest and, even today, one of the most popular.

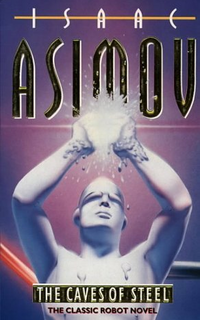

One of the delights of the locked room concept is its flexibility. You can adapt it for horror books, historical dramas, postmodernist fiction (see the Umberto Eco book below), or even science fiction—as Isaac Asimov shows in this pulp fiction novel from 1954. Asimov himself viewed science fiction in the most expansive terms—so I suspect he took particular delight in constructing a detective story set many centuries in the future. Adding to the fun, a human detective and robot investigator compete with each other in attempting to solve the mystery.

This is one of the finest works to come out of the Japanese locked room tradition, and boasts a beautifully elaborate plot. The novel comes complete with a fascinating metanarrative—a short story that predicts the murders, and is both included in the novel and is a key part of the unfolding investigation. Adding to the complexity, it takes forty years to solve the crime.